Israel Today Resources:

-

Hope Rising, Messianic Promise

Recommended donation: $20.00

Hope Rising, Messianic Promise

Recommended donation: $20.00

Add to cart

-

Song of Song: The Greatest Lover

Recommended donation: $18.00

Song of Song: The Greatest Lover

Recommended donation: $18.00

Add to cart

-

Divine Mysteries

Recommended donation: $15.00

Divine Mysteries

Recommended donation: $15.00

Add to cart

-

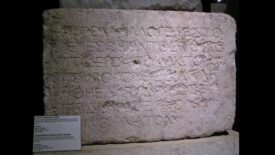

The Beauty of the Broken Wall

The Beauty of the Broken Wall

The early days of the Church were far more complicated and messy than many of us realize. As 21st century Bible readers, we tend to look back on the struggles and controversies of the 1stcentury Christians the way a backseat passenger describes a road trip: “Not much happened until we arrived.” But the driver knows better. He or she knows the twists and turns that led to the destination. When we read the Scriptures, we must understand that the conflicts of the early Church reveal much about God’s work among the first generation of Christ-followers, and about who we are called to be as the people of God now.

Perhaps the greatest controversy in the first few decades of the Christian movement was the full inclusion of Gentiles in the family of God. During the ministry of Jesus, Gentile God-fearers like the centurion at Capernaum (Matt. 8:5-13) and the Canaanite woman (Matt. 15:21-28) were welcomed and even upheld as examples of faith. But were these just exceptions to the norm? Were they merely fortunate outsiders who got to tag along because of the extravagant mercy of God?

When Jesus commissioned his followers to “make disciples of all nations” (Matt. 28:19-20), the scope of their mission became clear. The Kingdom of God was a kingdom for all who pledge allegiance to Israel’s crucified and risen Messiah. But how could this actually work?

First century Jews and Gentiles came from radically different backgrounds. Jews grew up saying the Shema and keeping the Sabbath and observing the food laws; most Gentiles participated in the Greco-Roman religious life that included temples, idols and civic sacrifices. When Jews and Gentiles from such different backgrounds were brought together by their shared faith in Jesus, it must have felt like a disaster in the making.

In his letter to the Ephesians, the Apostle Paul addressed the difficulty of bringing these two groups together. He reminded them that the death and resurrection of Jesus did far more than simply provide a shared faith. Through the work of Christ, Jew and Gentile Christ-followers are not only reconciled to God, but also reconciled to one another.

“For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to create in himself one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility.” Ephesians 2:14-16

Here Paul used a vivid image. In mentioning “the dividing wall of hostility” in verse 14, he was likely alluding to a particular structure in the courts of the Jewish Temple. The massive Temple complex in Jerusalem included colonnades and a sprawling courtyard where worshipers gathered, rabbis taught, and sacrificial animals were purchased. Moving closer to the Temple building, one came to a wall with this foreboding inscription: “No foreigner is to enter within the balustrade and forecourt around the sacred precinct. Whoever is caught will himself be responsible for his consequent death.”

This warning was a stark reminder that Gentiles were outsiders. In his letter, Paul leveraged the symbolic meaning of the wall and its warning to declare the full impact of the work of Christ. The death and resurrection of Jesus effectively tore down the barrier between Jews and Gentiles. By turning to Israel’s Messiah, Gentiles could now be reconciled to God and be welcomed into full membership in God’s family with Abraham’s faithful descendants. This is the theological basis for the multiethnic Kingdom of God.

In verses 19-22, Paul offered several illustrations to help the Ephesian Christians grasp their new identity as the reconciled people of God. First, they were fellow citizens of a new, everlasting kingdom (19a). The Roman Empire consisted of many ethnic groups, brought under the banner of Rome. The Kingdom of God, Paul said, was all that and far more. Second, they were members of God’s household (19b), new kind of family, adopted and brought together by the work of Christ. But then Paul compared this new people to a building.

He declared that Jesus is “the chief cornerstone.” The Greek word Paul used is “akrogoniaiou,” which can be translated two ways. It can refer to a cornerstone—the first stone set in for foundation, to which all the other stones must be aligned. Otherwise, the building will not be square. (See figure 1).But this word can also refer to the keystone of an arch. Here two different pillars rise up from different places, curving toward one another. These pillars would be unable to stand apart from the stone that joins them together at the apex of the arch. This keystone enables the arch to become a solid structure. (See figure 2).

Scholars argue over which translation should be preferred, but functionally Jesus can be compared to both. Like the cornerstone, He is the standard to which the Church must be in alignment. Whenever we find ourselves out of line with Jesus, we need to be corrected. But Jesus is also like the keystone that joins Jew and Gentile believers together, forming this New Covenant Community. We come from different places, but we are united by our shared faith in Jesus. This is what enables us to stand together.

One reason why I am so proud to support Israel Today Ministries is because it is a “cornerstone and keystone ministry.” Everything is done in careful alignment with message and methods of Jesus. But ITM is uniquely positioned to bring together Jew and Gentile Christ-followers in service to the Messiah. As we carry on the Lord’s work together, we gain a greater understanding of the heart of God and what it means to be called by His Name. – Dr. Doug McPherson, Lead Pastor, Mayfield Road Baptist Church, Arlington, Texas

Cornerstone graphic.figure 1 pdfKeystone graphic. figure 2 pdf

Cornerstone graphic.figure 1 pdfKeystone graphic. figure 2 pdf